The design of commercial box trucks is crucial in optimizing logistics and ensuring safety during transit. Among various design elements, the height of the box truck body plays a pivotal role in shaping its aerodynamic efficiency and fuel consumption rates. As logistics and freight companies, as well as construction and delivery service providers, strive to maintain competitive edges, comprehending how box truck body height influences wind resistance becomes increasingly important. This article will delve into five key areas: the direct effects of height on wind resistance, the correlation of aerodynamic performance with box truck body height, the implications of height on crosswind stability, fuel efficiency concerns under windy conditions, and innovations in design intended to minimize wind effects based on truck height. By exploring these dimensions, organizations can make informed choices to enhance their operations while addressing environmental concerns.

How Box Height Shapes Wind Behavior: Aerodynamics, Efficiency, and Stability in Commercial Trucks

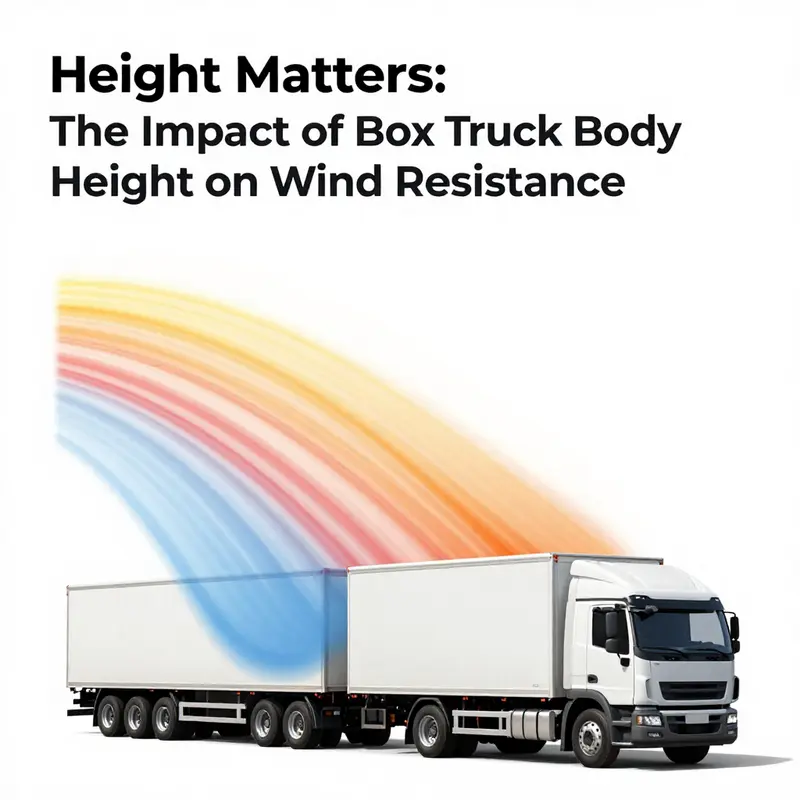

How height changes the way air behaves around a commercial box truck is central to efficiency and safety. A taller box creates a larger frontal area and becomes a blunt, or “bluff,” body that interrupts streamlines. That interruption raises pressure differences, enlarges wake regions behind the truck, and increases overall aerodynamic drag. At highway velocities, these effects are not marginal. Aerodynamic forces dominate fuel use and meaningfully influence handling.

When air meets the leading face of a tall cargo box, pressure builds up. That high-pressure zone resists motion and must be overcome by the powertrain. Over the sides and top, flow must accelerate to navigate around the obstacle. Where the flow cannot remain attached, separation occurs. A taller vertical surface gives a longer region over which separation can form. The separated flow behind the truck forms a low-pressure wake full of vortices and turbulence. This wake produces pressure drag, which grows rapidly with height and speed.

Drag scales with frontal area and the square of speed. Small increases in height raise frontal area and therefore increase drag in a near-linear fashion. But the drag coefficient itself can change too. A short, well-proportioned box may coax air to remain attached longer. A tall, sheer vertical wall forces abrupt detachment and a larger wake. The combination of increased frontal area and a worse drag coefficient amplifies total aerodynamic resistance.

The practical consequences are straightforward. Higher drag increases fuel consumption. Fleet operators notice this most on highways, where aerodynamic losses dominate rolling resistance and drivetrain inefficiencies. A modest increase in body height can translate into measurable fuel penalties over an annual mileage profile. Those penalties compound across fleet size and time, creating significant operating cost and emissions impacts.

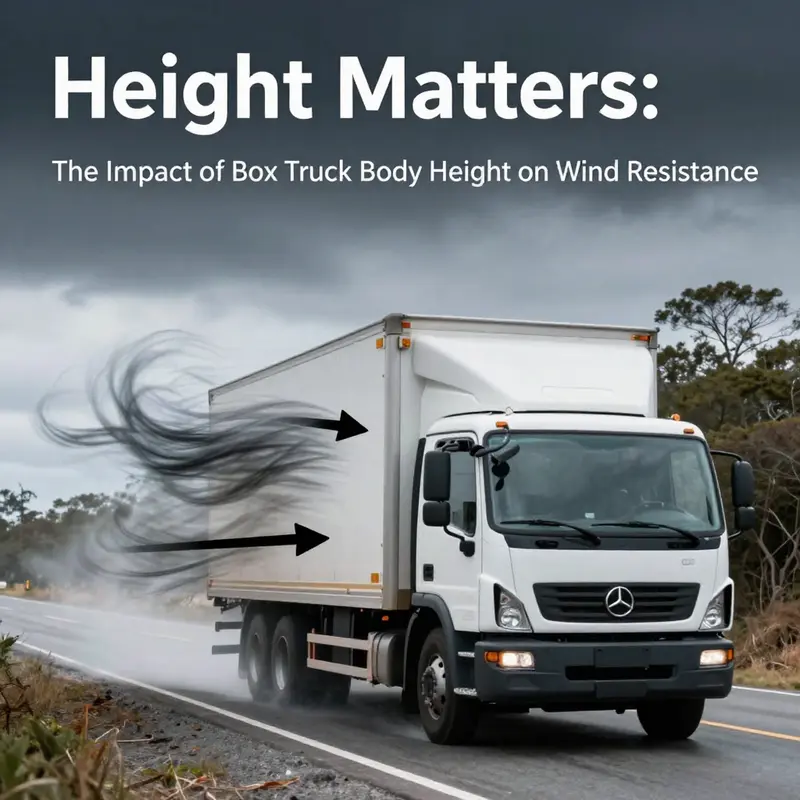

Height also affects crosswind sensitivity. A tall box presents more side area to lateral gusts. That side area acts like a sail, generating lateral forces and yaw moments that push the vehicle off heading. When crosswinds act on the upper surfaces, they create overturning moments that raise rollover risk. The higher the center of pressure relative to the center of gravity, the larger those moments become. Because taller bodies often raise a vehicle’s center of gravity, the two effects combine to reduce stability.

Speed interacts with both drag and stability. At highway speeds, aerodynamic moments scale up, making both fuel penalties and crosswind susceptibility more acute. On curves and lane-change maneuvers, a gust can quickly destabilize a tall truck if the design does not manage pressure distribution effectively. Drivers then face a harder task keeping the vehicle steady. For fleet managers, this means that height affects not only fuel bills but also safety margins and operational risk.

Designers have tools to manage these consequences without unduly sacrificing cargo capacity. Smoothing airflow with fairings and tapered transitions reduces separation and trims wake size. Roof caps, rounded leading edges, and sloped rear sections encourage attached flow and reduce vortex strength. Side-edge treatments help minimize the abruptness of flow detachment at corners. These treatments can lower the drag coefficient even if height cannot be drastically reduced.

Beyond add-on devices, geometric optimization of the box itself matters. Slight reductions in peak height can yield disproportionate aerodynamic gains. The goal is to minimize abrupt changes in curvature and to present gradual transitions to the approaching air. This can be achieved while preserving usable volume by redistributing internal space or by raising floor height slightly rather than increasing exterior height. Such trade-offs require careful analysis and often benefit from computational tools.

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and wind tunnel testing provide the means to quantify the impact of height variations. CFD models reveal where separation begins and how vortices form and interact. Wind tunnel data validate those models under controlled conditions. Together they guide targeted changes that reduce drag and improve stability. Trials that compare different roof profiles, edge radii, and rear devices consistently show that even modest shape changes reduce wake size and pressure drag.

Operational strategies also help mitigate height-driven penalties. Route selection, speed management, and timing can reduce exposure to strong crosswinds and sustain better fuel economy. Loading policies that keep the center of gravity low and centered reduce rollover risk. Regular maintenance to ensure aerodynamic devices remain intact preserves the performance benefits of design choices. Training drivers to anticipate and respond to gusts further reduces incident rates.

Regulatory and logistical constraints influence the practical limits of height reduction. Clearance requirements at bridges, loading docks, and distribution centers set minimum practical heights in some operations. Maximizing cargo volume while staying within those constraints pushes designers to seek subtle aerodynamic gains. Manufacturers and fleet planners must balance these constraints with aerodynamic priorities.

Cost considerations shape which solutions are adopted. Add-on fairings and roof caps are relatively low-cost steps with measurable returns through fuel savings. More extensive body redesigns or changes to chassis height carry higher upfront costs. Fleet life cycles and total cost of ownership models determine whether investments in lower-profile bodies or aerodynamic retrofits make sense. Market pressures and orders for trailers also affect how quickly manufacturers prioritize lower-profile or more aerodynamic designs, as seen in industry shifts and manufacturing responses.

Height optimization also influences environmental performance. Lower drag reduces fuel use and tailpipe emissions. For fleets seeking to meet emissions targets or improve sustainability metrics, managing vehicle height becomes another lever. Combined with drivetrain advances and operational improvements, height-conscious design supports longer-term decarbonization goals.

Safety, cost, and emissions are connected through aerodynamic performance. A taller box increases drag and crosswind sensitivity. That raises fuel costs, operational risk, and environmental impact. A coordinated approach that blends geometric refinement, add-on fairings, CFD-guided design, and operational best practices yields the strongest outcomes. By treating height as a variable to be optimized rather than a fixed constraint, fleets and manufacturers unlock gains across multiple dimensions.

Finally, the interplay between market forces and engineering choices should not be overlooked. Manufacturers respond to demand for capacity, cost efficiency, and regulatory clarity. When markets prioritize lower operating costs and safety, design trends shift toward sleeker, lower-profile enclosures. For context on how the industry adapts to changing market conditions and manufacturing strategies, refer to this discussion of the trailer market crisis and manufacturers’ strategies: https://truckplusllc.com/trailer-market-crisis-manufacturers-adapt-strategies/.

For a rigorous technical examination of how geometric factors including height alter aerodynamic performance, see the detailed CFD and experimental study here: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S235248472300169X

Raising the Roof: How Box Truck Height Shapes Wind Drag, Stability, and Fuel Economy

The height of a commercial box truck is more than a number on a spec sheet. Each extra inch in cargo enclosure height increases the frontal area exposed to oncoming air, turning a simple box into a bluff body that challenges smooth flow. When a vehicle moves at highway speeds, even modest increases in frontal area translate into noticeable drag. The effect compounds because the flow around a tall, boxy profile separates more readily, creating larger wake regions and vortices behind the truck. This isn’t guesswork; CFD simulations and wind-tunnel experiments consistently show that the height of the box is a primary determinant of aero drag and overall efficiency. The connection isn’t solely about fuel economy; it also touches handling and stability, especially in gusty conditions where larger crosswind forces act on a higher center of gravity and greater side area.

The physics are straightforward yet nuanced. A taller box expands the vehicle’s cross-section in the direction of travel, enlarging the pressure drag component of total drag. The airflow facing the box slows and diverts around the edges, and separation points migrate forward and aft depending on the curvature of the front face and the sharp corners of the cargo enclosure. The result is a wake full of turbulent eddies that propagate pressure differences down the length of the trailer and tractor. In the precise terms of aerodynamicists, the taller the body, the greater the potential for flow separation at the front corners and near the roofline, which then seeds a stronger vortex system along the sides and rear. This not only elevates drag but also increases unsteady loading on the truck. These dynamics are especially pronounced at highway speeds where the kinetic energy of the airstream is high and any drag penalty is multiplied by distance traveled.

The distribution of forces along the vehicle further illuminates the height effect. The front face interacts with the air, but the top corners and the flat roof create a broad surface that encourages air to reattach or detach in ways that form a large, stubborn recirculation zone. That recirculation raises pressure on the forward half and pulls airflow away from the bottom, altering how the air re-energizes around the vehicle as it moves. The rearward half sees extended separation zones, where low pressure and swirling flow intensify under the roof edge. This is the classic wake of a bluff body, and it is exactly what wind tunnel data and CFD studies quantify in terms of drag coefficient and overall resistance. The practical implication for operators is straightforward: a taller box often means more fuel burned per mile, all else equal, particularly when routes include long highway segments at sustained speeds.

The research also clarifies where to focus optimization work. Studies that examine small box-type trucks using CFD identify front and top regions as the most sensitive to height changes. These zones are where the flow first negotiates the abrupt geometry of the cargo enclosure, making them prime targets for strategies that reduce separation or reconfigure the flow path. The elegant finding in this body of work is that improvements do not require a wholesale redesign of the chassis; rather, targeted shaping and the strategic placement of fairings can yield meaningful drag reductions. In fact, well-designed aerodynamic fairings across various sections of the vehicle have demonstrated up to about 26% drag reduction in some configurations. While that level of reduction depends on baseline geometry and the material choices for the fairings, the magnitude illustrates how sensitive aero performance is to even modest changes in height-related flow features.

The front and top regions, in particular, benefit from optimization because they are the interfaces where the air first meets the elevated surface. A refined front nose can streamline the oncoming flow, guiding it to stay attached longer and reducing the intensity of separation at the crown. On the top, adding fairings or shaping features that smooth the transition from the main body to the upper corners helps to tame the dominant vortices that would otherwise wrap around the roofline. CFD-driven approaches, which derive local optimum criteria from the flow field topology, provide a disciplined method to decide where and how to modify geometry. This means that aerodynamic improvements are most effective when they align with the actual flow patterns rather than relying on generic, one-size-fits-all trims. The practical payoff is more than just a number on a wind tunnel chart. It translates to cleaner airflow, less pressure drag, and, crucially, lower fuel consumption on long routes.

Beyond drag for fuel economy, the height of a box truck has safety implications that operators cannot ignore. Tall bodies present larger side areas and higher crosswind moments. In gusty conditions, crosswinds can push a box truck sideways, generating yaw moments that strain the steering system and test the driver’s skill. The risk is not merely that the truck may drift; it can also lead to sudden, dangerous roll tendencies when the gusts hit at the aerodynamically sensitive parts of the body. The combination of a high center of gravity for some configurations and the broad planform exposed to gusts means that aero design and stability must be considered together. Regulations and testing regimes increasingly emphasize stability margins, and manufacturers are keen to balance the benefits of more cargo height with the realities of wind-induced loads. Thus, aerodynamic refinements that reduce drag without compromising structural integrity become doubly valuable.

For operators, the takeaway centers on consistency and route planning. When a fleet uses taller box bodies, fuel planning must account for the higher drag seen at highway speeds. The difference might be modest on a short urban run, but on a cross-country route, the cumulative fuel penalty can be substantial. The best practical path is a combination: where possible, reduce height without sacrificing cargo volume, apply surface treatments and fairings that minimize drag, and rely on drive-cycle strategies that mitigate high-speed exposure where conditions allow. The lesson extends beyond single-vehicle improvements. Fleets that adopt aero-aware specifications in procurement—favoring streamlined shapes, lower profiles, and components designed with flow in mind—can realize compounded gains across entire operating days. The synergy between vehicle geometry and weight distribution matters, as a well-turned design reduces the energy needed to push air out of the way, leaving more energy for actual propulsion and payload performance.

The scientific record underpinning these points is clear and increasingly precise. CFD simulations provide a virtual wind tunnel where the complex geometry of a box truck is tested across a wide range of speeds, yaw angles, and surface roughness conditions. Wind-tunnel experiments complement these simulations by validating how small geometry tweaks translate into measurable drag changes. The joint conclusion across studies is that height is not a marginal parameter. It plays a central role in how air navigates the vehicle, where it separates, and how quickly turbulence decays downstream. The practical directive is to treat height not as a single linear measure but as a coupling factor that interacts with curvature, edge refinement, and the distribution of auxiliary components on the roof and sides.

For those who seek concrete design pathways, the literature points to a few decisive moves. Start with refinements to the front face and roofline, where the highest potential for drag reduction exists. Add carefully placed top and side fairings to keep the flow attached longer and to suppress the strong vortices that form around the corners. When possible, re-evaluate the position and shape of rooftop boxes or other protrusions that disrupt the lateral flow. The goal is to reduce the wake and to minimize areas where the air recirculates into the vehicle’s immediate vicinity. The approach is sustainable, too: by lowering drag, the vehicle consumes less fuel, emits fewer pollutants, and travels a bit farther on the same amount of energy. The effect compounds over the lifetime of a commercial fleet, making a height-aware approach a cornerstone of modern aero optimization.

In closing, the study of box truck aerodynamics shows that height is a central lever, not a marginal detail. Taller bodies create more drag, increase destabilizing wind effects, and demand higher engine output to maintain speed. Yet height is also a field where practical changes can pay off quickly. The combination of front-face refinements, top-region fairings, and topology-informed geometry modifications offers a path to meaningful drag reductions—without compromising capacity or safety. For readers who want to see a rigorous treatment of how flow field topology informs drag optimization in box-type trucks, the comprehensive study linked earlier provides a robust blueprint for applying CFD-driven insights to real-world designs. In the end, height-aware aerodynamics is about balancing cargo needs with the physics of air. It is a reminder that the shape of a box truck is not a cosmetic choice but a functional decision with consequences for efficiency, reliability, and environmental impact.

The broader fleet context also matters. A parallel thread of industry analysis argues that optimizing height and aerodynamics integrates with freight economics, driver training, and maintenance practices to yield the largest gains when pursued as a coordinated program. That means not only choosing a lower height where feasible but also investing in roofline streamlining, fairing geometry, and consistent surface finish to minimize roughness-induced drag. For further reading on how flow topology informs drag optimization in box-type trucks, a detailed, peer-reviewed exploration offers a rigorous framework you can adapt to real-world design decisions. Trailer orders, margins, and procurement considerations intersect with aerodynamics through total cost of ownership, route planning, and maintenance strategies. This integrated view helps bridge the gap between the physics of air and the daily realities of fleet operations Trailer orders impact truckload margins.

External resource: https://doi.org/10.1504/ijvp.2023.10058001

Tall Walls, Turbulent Winds: How Box Truck Height Shapes Crosswind Stability and Road Safety

Crosswinds pose a persistent hazard for commercial box trucks, especially when the cargo enclosure stands tall behind the cab. Height directly feeds into the vehicle’s aerodynamic footprint. A higher box increases the frontal area presented to the oncoming flow and promotes the formation of a pronounced bluff body. The air is interrupted earlier and more aggressively along the sides, the top, and the rear corners, which spawns a wake that extends farther down the road. In practical terms, this means greater aerodynamic drag at equivalent speeds and more pronounced flow separation when gusts hit. The resulting pressure distribution around the truck becomes uneven, and that unevenness translates into lateral forces that steer the vehicle toward the windward side. The interaction is most acute at highway speeds where a gust can persist long enough to impose a sustained yaw moment. In short, height magnifies wind-related effects not just on fuel use but on handling and stability during gusty events.

Center of gravity is another critical piece. A taller cargo box raises the truck’s overall center of mass, and with heavy loads that center is pushed higher still. Even with a well-balanced axle load, the vertical distribution of weight alters how the vehicle responds to lateral wind. A higher center reduces the natural self-righting tendency of the chassis, increasing the likelihood that a sudden gust will push the vehicle toward the outside of a curve or into the adjacent lane. This is especially dangerous in exposures such as bridge decks, exposed highway sections, or where wind accelerates as it funnels through tunnels and structural gaps. Experimental and field studies consistently show that high-sided vehicles have elevated rollover risk under comparable crosswind conditions, underscoring why height is treated as a safety-critical parameter in both design and operation.

Asymmetrical aerodynamic responses add another layer of complexity. When a crosswind encounters a tall box, the flow around the left and right sides does not mirror perfectly. Driving-simulator work has demonstrated that a leftward gust can cause greater lateral displacement than a rightward gust at the same wind speed, a result that reflects real-world asymmetries in surface roughness, corner geometry, and wake development. For operators, this means that routine handling practices cannot assume perfect symmetry in gust response. For designers, it means that stability margins must account for directional bias in crosswind loading, and that testing should cover gusts from multiple directions. The net effect is a more nuanced view of stability that blends vehicle geometry with wind directionality rather than treating crosswinds as uniform loads.

From a physics perspective, the yaw moment is the primary factor eroding stability in tall bodies. As the wind interacts with a higher surface, the pressure field around the front corners and along the top tends to push the vehicle into a sideways rotation. Lift forces on the sides and the subtle changes in vertical forces across axles compound this effect, altering the pitch and roll coupling in ways that are not obvious from straight-line acceleration tests. The taller the box, the larger the area over which pressure acts, and the earlier flow separation occurs on the vehicle’s midsection. The result is a stronger, less predictable yaw response that makes lane keeping harder and increases the chance that the rear end will shed its grip on the ground during a gust.

Aerodynamic modifications offer a path to dampen these effects without sacrificing payload. Research indicates that devices placed on the top and sides of the trailer—designed to guide airflow, reattach separated flow, and suppress wake formation—can improve stability. The key point is that these gains can come with a modest increase in overall dimensions, often less than about 1 percent, meaning the vehicle can retain most of its payload capacity. Of course, every added device carries maintenance implications and potential debris risk, so the design process uses a careful trade-off analysis. In practice, engineers balance drag reduction, stability gains, environmental impact, and lifecycle costs to identify configurations that deliver safety benefits in gusty conditions while remaining robust on busy routes. The goal is to tilt the aerodynamic balance toward smoother flow with less crosswind-induced rotation.

Safety regulations and best practices frame these design efforts in a real-world context. Operators must respect cargo-height limits to prevent under- or over-specifying the envelope, yet they also execute loading procedures that keep weight evenly distributed and not top-heavy. Even with optimized aerodynamics, the driver’s task remains to reduce speed before curves and windy stretches, to choose lanes with gentler crosswinds where possible, and to anticipate gusts near restricted wind channels like bridges and tunnel exits. The emphasis on proactive management reflects the variability of wind and the difficulty of predicting gust intensity. In this environment, height management is part of a broader safety culture that combines vehicle design, route planning, and driver training to minimize the probability and severity of wind-induced incidents.

Design improvements by manufacturers emphasize a holistic approach. By enhancing chassis stability, refining suspension dynamics, and adopting intelligent weight distribution strategies, the vehicle can better withstand lateral disturbances. These improvements do not stand alone; they interact with the box height to shape the overall handling envelope. A lower center of gravity can compensate to some extent for a tall deck, while a taller deck may require stiffer suspension to restrain roll. The practical message is simple: reduce the propensity for wind to induce yaw by aligning the aero profile with the vehicle’s structural dynamics, rather than treating the box in isolation. The outcome is not only safer handling but a more predictable response to wind across a range of speeds and routes.

From the perspective of design philosophy, height should be treated as a primary parameter in aerodynamic modeling, not a postscript. A lower, more streamlined cargo height reduces head-on drag and the drag in the wake behind the trailer, and it reduces the height at which high-energy vortices form in crosswind conditions. Yet, the needs of cargo and regulatory limits cannot be dismissed. The optimal solution often involves modestly lowering the enclosure height while employing targeted aerodynamic features that tame the flow at critical regions, such as the front corners and the trailing edges. In practice, designers use a combination of computational simulations and wind-tunnel data to adjust the balance of height and devices until the vehicle exhibits smoother, more controllable behavior in crosswinds. The literature shows that even small reductions in height can have outsized effects on stability when paired with carefully placed devices that shape both the upwind and downwind flows.

Beyond fixed geometry, there is growing interest in smarter chassis concepts that adapt in real time to wind conditions. It is here that a broader body of work on trailer and tractor-trailer dynamics begins to pay off practical dividends. The potential to damp yaw through adaptive surfaces or active suspension logic offers a path to maintaining lane position even when gusts peak. While the technical specifics vary, the underlying principle remains the same: height is a lever, but it performs best when combined with dynamic control strategies and route-aware operation. For practitioners, this translates into an invitation to consider how height, air flow, and chassis control interact in a single system rather than in isolation. The linked discussion on aero-vehicle devices provides a concrete example of how end-effectors can be integrated into a taller envelope to temper wake and lift distributions.

Validation through wind tunnel experiments and CFD is crucial to grounding these ideas in reality. The evidence shows that the interaction between box height, flow separation, and wake turbulence becomes more pronounced as height grows. The presence of front and rear aerodynamic devices can modulate these effects by reducing separation at the front, reconfiguring the rear wake, and lowering the peak yaw moment during gusts. In practical terms, the test data translate into lower crosswind tendencies and better controllability for drivers who confront wind corridors on open roads.

These findings feed into a safety ecosystem that includes regulators, designers, and operators. Regulations establish height limits and ensure predictable performance within those bounds. Operators apply loading guidelines, route planning, and operating speeds that reflect wind exposure. Designers translate these constraints into innovations that preserve payload and safety, while offering a more forgiving response to crosswinds. The synergy among these actors is essential, because the wind does not respect category lines; it tests the entire system from the cargo box to the driver’s hands on the wheel.

Taken together, the central takeaway is practical and actionable: optimize the cargo height within the payload envelope, complement it with aerodynamic features that actively manage flow, and couple this with driver training and route planning. The combined effect is lower drag, reduced fuel consumption, and noticeably improved stability in wind. In weather-prone corridors, even small improvements compound into meaningful reductions in risk and environmental impact.

As a final note on evidence, the wind-tunnel study on front-rear aerodynamic devices provides a rigorous demonstration of how flow control at both ends can modulate the wake and influence lift distribution across a tall envelope. This work sits alongside CFD results to give engineers and operators a coherent picture of how height, devices, and gusts interact across a range of speeds and wind profiles.

Online resources and professional syntheses continue to emphasize height as a design parameter that should inform route selection, maintenance planning, and training. When height is treated not as a fixed constraint but as a variable to optimize, crosswinds become a problem that can be managed rather than a risk to be endured.

For technical validation, see https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014272662300059X.

Raising the Bar, Lowering the Drag: How Box Truck Height Shapes Wind Performance and Fuel Economy

Air moves around a moving box truck as if it were a living landscape—sometimes smooth, often turbulent. The height of the cargo enclosure acts like a vertical sail and a bluff obstacle at once. In windy conditions, the taller the body, the larger the frontal area presented to the oncoming flow. That increased exposure raises aerodynamic drag, forcing the engine to labor to maintain speed. The relationship is not merely theoretical: wind tunnel tests and computer simulations consistently show that even modest reductions in height can translate into measurable improvements in efficiency. For fleets faced with long hauls and variable weather, height becomes a practical lever. The physics are straightforward on the surface but revealing when you look at the details of how air negotiates a tall, boxy profile and then separates behind the vehicle, creating vortices and pressure drag that persist far down the road.

When wind meets a tall box truck, the encounter is dominated by the shape it presents to the wind. A high side wall and flat front increase the cross-sectional area that air must pass around. The result is a stronger stagnation zone at the front and larger regions of flow separation along the sides and rear. The air that cannot be steered smoothly around the vehicle must be accelerated and shed in the wake. This wake is turbulent, and its pressure drag grows with the height of the body. The effect compounds at highway speeds, where even small increments in drag demand more engine power and burn more fuel. In practice, a higher profile translates into higher fuel consumption over a given distance, especially when the wind does not cooperate with the vehicle’s motion. The simplest takeaway is that every inch trimmed from the cargo enclosure can contribute to lower fuel use, smoother handling, and quieter operation, which matters for driver satisfaction and fleet economics alike.

The evidence comes from multiple lines of inquiry. CFD studies model air flow around virtual trucks with different cargo heights, revealing how reduced height limits air separation and suppresses large-scale vortex formation near the rear corners. Wind tunnel experiments corroborate these findings, showing that even small changes in body height alter the pressure distribution across the vehicle. The practical implication is clear: a lower-profile box truck can slice through the air more cleanly, with less energy diverted into overcoming drag. This is especially true when the truck travels into headwinds or through gusty crosswinds, where the interaction between body height and wind angle magnifies the drag penalty. In simple terms, less height means less air to push out of the way and a smaller wake to contend with after the vehicle passes.

A concrete example helps ground the discussion. Consider a 14-foot box truck used for construction materials or landscaping supplies. Its enclosed, rectangular cargo area is efficient for securing goods, yet the tall side walls and flat front contribute to a relatively tall bluff body. In sustained wind, that geometry imposes a noticeable drag load on the powertrain, pushing up fuel consumption. Reducing height—whether by reshaping the cargo space, adopting aerodynamically contoured side rails, or employing a tighter tarping system to minimize exposed surface area—can yield immediate aerodynamic dividends. The savings accumulate over long routes and across fleets, reinforcing the business case for height optimization as part of a broader efficiency program. This is not just about geometry for geometry’s sake; it is about disciplined design choices that align regulatory limits with performance goals and environmental stewardship.

The wind does not see height in isolation. The rear geometry, for example, plays a crucial role in how the flow reattaches or remains detached as the vehicle moves forward. High rectangular bodies tend to foster stronger rear separation, which sustains pressure drag well into the vehicle’s wake. In contrast, a lower, more smoothly contoured rear profile helps air rejoin the main flow sooner, reducing turbulent energy in the wake and diminishing the drag penalty. The combined effect of a taller front and a more abrupt rear can significantly degrade overall aerodynamic efficiency, particularly on long, straight road segments where wind effects persist for miles. The aerodynamic story is thus a sequence: height shapes the frontal interaction, height and rear geometry govern wake behavior, and both together determine the steady-state drag that the engine must overcome to keep pace with traffic.

From a safety perspective, height matters beyond fuel economy. Box trucks operate across a spectrum of weather, road crowns, and crosswinds. Taller vehicles are more susceptible to side gusts, which can produce torque and lateral forces that challenge stability. In strong gusts, a higher body height increases the likelihood of larger side pressures and transient tipping moments, raising concerns for rollover risk, especially when the vehicle is heavily loaded or traveling through exposed terrain. Aerodynamics and stability are linked in this sense: as drag rises, the vehicle’s energy reserves shift from forward propulsion to maintaining directional control. For operators, the takeaway is not only to chase fuel savings but to understand how height interacts with load distribution and driving conditions to affect handling and safety margins on the highway.

The regulatory backdrop adds another layer of nuance. Maximum dimensions are constrained for reasons of highway safety, traffic compatibility, and structural integrity. Within those constraints, reducing height remains a practical strategy for improving efficiency without sacrificing cargo capacity or security. Fleet managers can pursue height optimization alongside other aerodynamic improvements, such as side rails designed to guide airflow more smoothly along the vehicle’s profile or tarps that minimize exposed drag without compromising cargo access. The overarching principle is straightforward: any reduction in aerodynamic resistance, even if it seems modest, compounds across miles and hours, yielding meaningful cost savings and emissions reductions over time. This approach harmonizes regulatory compliance with performance engineering and environmental responsibility, turning a height decision into a strategic operational choice.

For fleet operators weighing the economics of height optimization, the numbers can be compelling. The initial costs of modifying a cargo enclosure or adopting new, lower-profile components must be weighed against anticipated fuel savings, reduced maintenance strain from smoother airflow, and improved stability in adverse wind conditions. The payback period hinges on route characteristics, typical wind exposure, and annual mileage, but the intuitive logic remains solid. Short-term capital investments can translate into long-term operating savings, reinforcing the business case for prioritizing aerodynamic height as part of a comprehensive efficiency plan. It is not a one-off tweak but a disciplined, long-range strategy that aligns with broader goals of lower total cost of ownership, reduced emissions, and more predictable operating margins. In this sense, height is a design parameter with real consequences for the bottom line, not merely a matter of cargo configuration.

To connect this aerodynamic perspective with broader industry dynamics, industry observers note that any efficiency program benefits from cross-functional alignment. Height decisions intersect with maintenance practices, load planning, and driver training. When engineers, fleet managers, and drivers share a common understanding of how tall bodies behave in wind, they can implement coordinated strategies—such as selecting routes with favorable wind profiles, scheduling deliveries to minimize exposure to gusty conditions, and using weather-informed driving practices—that collectively enhance performance. The practical path forward blends physical design with operational discipline, turning an aerodynamic insight into tangible improvements in daily fleet productivity. For readers seeking to blend theory with practice, one illustrative link points to industry analyses on how trailer and body design choices influence overall truckload economics, illustrating how aerodynamic considerations fit into broader cost-management strategies: Trailer orders impact truckload margins.

Beyond the specifics of height, the broader take-home message is that wind performance emerges from a suite of design choices that, when bundled together, yield meaningful gains. Reducing height is not a panacea; it must be balanced with cargo needs, structural integrity, and regulatory compliance. Yet it remains a robust lever, with aerodynamic effects that are both measurable and repeatable across fleets. As manufacturers and operators continue to push toward lower, more streamlined profiles, the momentum behind height optimization reflects a pragmatic convergence of physics, economics, and safety. The ultimate goal is a road system where box trucks move with less drag, less fuel burn, and greater resilience in wind, delivering the same essential service with a gentler footprint on drivers, communities, and the environment.

External reference: For a deeper technical treatment of how body height influences aerodynamic performance, see the following study: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S096809092300175X

When Height Meets Gusts: How Box Truck Body Height Shapes Wind Drag, Stability, and Fuel Efficiency

The relationship between box truck height and wind is not simply a matter of tall versus short. It is a complex interplay between frontal area, bluff body effects, flow separation, and the wake that trails the vehicle. When the cargo enclosure stands taller, the vehicle presents a larger cross-section to the airstream. This bigger footprint amplifies pressure drag and creates more extensive regions where air swirls and detaches from the surfaces. In practical terms, taller bodies disrupt smoother airflow, generate stronger vortices at the rear, and increase the overall energy the engine must supply to maintain highway speeds. The literature across high-speed flow studies—from wind tunnels to computational simulations—consistently shows that the height of a boxy, rigid enclosure is a primary driver of aerodynamics. The result is a rise in fuel consumption, reduced performance at cruising speeds, and a heightened sensitivity to gusts that can challenge stability on highways and open stretches of road.

Wind interacts with a tall box truck in several distinct ways. At the front, the bluff shape creates a pronounced stagnation zone, where pressure is higher than in the surrounding air. The air then tries to negotiate the sharp edges of the cargo box, and as it does, it separates from the surface. This separation seeds a trail of turbulent air that forms a complex wake behind the vehicle. The wake industry professionals study is not merely academic. It governs the real-world drag penalty, the tendency for the vehicle to pull sideways in gusts, and the manner in which the vehicle must wrestle with crosswinds at highway speeds. In this sense, height is not a cosmetic attribute; it is a functional variable that conditions the vehicle’s entire aerodynamic signature.

The practical consequences reach beyond fuel economy. When wind loads rise, so does the demand on chassis integrity and the structural joints that hold a tall cargo enclosure aloft. A higher center of gravity can magnify moment arms created by lateral gusts, making steering corrections more challenging and, in some wind events, increasing the risk of loss of control. This is not a remote risk; operators report that gusty crosswinds can surprise even experienced drivers, particularly in exposed corridors or open rural highways where buildings and trees do not buffer the flow. The physics is clear: height amplifies the wind’s leverage on the vehicle, and the consequences cascade from drag and efficiency into safety margins and operational reliability.

As the height grows, the air around the rear corners of the box tends to roll into larger vortices that shed away from the truck. These vortices contribute to a turbulent wake that can interact with passing traffic in dense flows and, more critically, magnify drag as the vehicle speeds up or slows down. The drag penalty is most pronounced at highway velocities where the powertrain must overcome persistent resistance. This is not merely a matter of more fuel per mile; it also translates into greater heat generation, more pronounced engine load variations, and potentially higher maintenance demands for engine cooling systems at peak operation.

The consistent message from aerodynamic research—though not always framed in the trucking industry vernacular—is that reducing or reshaping the height can yield meaningful gains. CFD simulations and wind-tunnel validations, though sometimes applied to diverse structures, share a common thread: any measure that reduces flow separation and minimizes wake complexity tends to improve overall performance. In the context of commercial box trucks, this means that even modest reductions in height, or the adoption of shaping features that mimic streamlined profiles, can help align the truck’s aerodynamic performance with more favorable fuel economy and steadier behavior in gusty conditions. In other words, height acts as a lever for aerodynamics, not merely a dimension to be managed for cargo capacity.

Despite the absence of a cataloged set of truck-specific innovations in the sources at hand, the broader wind mitigation playbooks offer transferable ideas. Tall structures, for instance, incorporate mechanisms that diffuse wind pressures and reduce the abrupt forces generated by gusts. Techniques like wind-friendly floor layouts, which allow flow to pass through or around structural elements to flatten pressure differentials, illustrate a fundamental principle: guide the air instead of trying to conquer it with sheer mass. In large infrastructure and equipment contexts, designers pursue flow management through carefully tuned geometries, which can be adapted, at least conceptually, to the geometry of a box truck. The core idea is to avoid abrupt separations and to shape surfaces so that the boundary layer adheres longer, thereby limiting the formation of large, energetic vortices.

A practical extrapolation from these wind-mitigation principles is that aerodynamic improvements do not require radical redesigns of the cargo box; instead, they can emerge from a holistic reading of the vehicle’s shape and surface interactions. Smoothing transitions between the cab and the cargo box, rounding corners that otherwise promote separation, and smoothing underbody contours are steps that align with both aerodynamic theory and what modern manufacturers pursue in broader vehicle development. Even small changes—such as more seamless junctions, improved edge finishes, and softer transitions at the roof line—can reduce harsh flow separation and lessen wake intensity behind the vehicle. These are not miracles of engineering, but they are well-supported steps that align with the general principle of reducing bluff body effects through careful shaping.

This line of thought naturally leads to the broader concept of active and passive aerodynamic features. Passive features include fixed fairings, rounded corners, and continuous surface coverage that minimize abrupt changes in flow direction. Active approaches—such as adjustable ride heights or adaptive panels—are more speculative in the box-truck domain but share the same objective: to keep the vehicle’s aerodynamics tuned to the current wind conditions and speed. The literature on other heavy-duty contexts hints at the potential for dynamic systems that respond to wind loads in real time, adjusting the external geometry to maintain a lower drag state. While not demonstrated specifically for box trucks in the present materials, these ideas illustrate how height, shape, and airflow concepts can come together to influence performance.

The chapter’s core takeaway is that height is a central variable in wind interaction, and its effects cascade into fuel efficiency and safety. Yet height does not operate in isolation. It interacts with the vehicle’s overall silhouette, the sharpness of edges, the presence or absence of protective underbody components, and the way cargo is enclosed and secured. These interactions determine how much air stays attached to the surface, where separation occurs, and how turbulent the wake becomes at different speeds and wind directions. Operators and designers can, therefore, think about height not only as a constraint on cargo volume but as a design parameter that can be tuned in concert with other aerodynamic features to achieve better performance without sacrificing essential capacity.

To connect these aerodynamic considerations with the practicalities of the industry, consider how height intersects with market dynamics like trailer orders and margins. The shipping environment is shaped by demand, capacity, and the cost of operation—sensitivities that are intensified when energy efficiency improves. In this context, even incremental aerodynamic improvements can translate into meaningful savings across fleets and fuel budgets. If a carrier can achieve measurable gains in fuel economy through thoughtful height management and surface design, that advantage compounds as miles accumulate and routes vary in wind exposure. The decision to pursue height adjustments, therefore, becomes a strategic balance between cargo needs, regulatory constraints, and the potential for aerodynamic payoffs that align with bottom-line pressures. For readers tracking how the broader market is evolving, this crossroad highlights how seemingly technical choices reverberate through economics and operations. The trailer orders and margins discussion, in particular, provides one lens through which to view the practical implications of taller bodies in today’s market—and how height-driven aerodynamics can become a differentiator when leveraged with disciplined engineering and fleet management.

Ultimately, the path forward lies in embracing the physics while pursuing pragmatic design and operational strategies. The research landscape suggests that there is room to translate broad wind-mitigation ideas into concrete, truck-specific solutions that respect cargo needs and regulatory realities. The absence of a dedicated compendium of box-truck innovations in this set of results should not be mistaken for impossibility. Instead, it signals an opportunity for cross-pollination: engineers can borrow from wind-tacing concepts used in tall structures and large infrastructure, while truck designers adapt these insights to the scale and constraints of commercial freight. The result could be a family of design concepts that preserve cargo height where required while moderating wind effects through refined shaping, surface treatment, and, where admissible, adaptive features that respond to real-time wind loading. The wind, after all, is a persistent partner in the road freight equation. Recognizing its influence on height and architecture is the first and perhaps the most practical step toward safer, more efficient operations on a windy highway.

For readers seeking a concrete touchpoint in the industry narrative, consider how market trends around trailer orders and margins shape the adoption of any aerodynamic refinements. The broader dialogue about efficiency and safety in tall-bodied freight continues to evolve, with height acting as a central, but not solitary, determinant of wind behavior. As fleets compare the trade-offs between cargo capacity and fuel economy, the aerodynamics of height become a focal point for decision-making. The narrative around wind and height is not merely technical; it is a practical guide for operators and designers who must balance competing demands in real-world conditions. In that sense, height-aware design is less about chasing a perfect ideal and more about achieving resilient performance across a spectrum of speeds, winds, and road types.

External reading can offer further clarity on wind effects beyond the trucking domain. For a broader perspective on wind and vehicle aerodynamics, see a comprehensive overview at an external resource that expands on how flow control, drag reduction, and wake management operate in complex flow environments. External aerodynamic resource. In the context of box trucks, these principles sharpen the understanding that height is a lever, not a limit, and that targeted shaping and strategic integration of aerodynamic elements can yield meaningful, fuel-related dividends without sacrificing payload or profitability.

To tie this back to the practicalities of industry communications and knowledge sharing, a linked discussion about the evolving market and its impact on operations can be found in industry analyses that explore how trailer orders affect margins. Trailer Orders Impact Truckload Margins. This internal reference helps illuminate how aerodynamic considerations, including height, sit within a broader decision framework—one where engineering insight must harmonize with market signals to deliver tangible gains on the road.

Final thoughts

Understanding how the height of a commercial box truck body affects wind resistance can be a game-changer for logistics and procurement strategies. The correlation between truck height, aerodynamic performance, crosswind stability, and fuel efficiency highlights the importance of thoughtful vehicle design in optimizing operational efficacy. As technology advances, design innovations continue to emerge, allowing companies to safeguard against the adverse effects of height on wind resistance, enhancing both safety and sustainability. Stakeholders are encouraged to consider these insights when procuring or designing box trucks, ultimately leading to more efficient and environmentally conscious operations.