In the realm of logistics and construction, the classification of vehicles is critical to compliance, insurance, and operational efficiency. Trucks fitted with ladder racks, which serve as practical tools for transporting long materials and equipment, often raise questions about their commercial status. This article delves into the essential factors that influence whether a ladder rack-equipped truck qualifies as a commercial vehicle. It offers a structured exploration, beginning with an understanding of commercial classification, moving to the implications of business usage, and discussing regulatory and insurance guidelines. The economic effects of classifying such vehicles and a comparative analysis with other commercial vehicles further enhance our comprehension of this topic. Each chapter is designed to provide actionable insights for company owners and procurement teams navigating this complex landscape.

Beyond the Rack: Decoding When a Truck with a Ladder Rack Becomes a Commercial Vehicle

A ladder rack on a truck is a useful tool, not a magic badge of business status. Many owners assume that adding a cargo accessory somehow shifts the vehicle into a different regulatory category. In truth, the classification hinges on two intertwined forces: the vehicle’s structural weight characteristics and the purpose for which it is used. The ladder rack itself is an aftermarket enhancement that increases utility. It does not, by itself, redefine a light pickup into a commercial machine or transform a personal project into a commercial fleet operation. But the line between personal and commercial use is not a simple line drawn at the rack. It bends around the weight a vehicle can carry, how that weight is distributed, and how the vehicle is employed on a regular basis. To understand where a ladder rack fits in, we must look at the structural language of the road—the Gross Vehicle Weight Rating, or GVWR, and the context of use that turns a tool into a business practice.

The GVWR is the primary determinant in most regulatory frameworks. It marks the maximum total weight the vehicle is designed to carry, including the weight of the vehicle itself (the curb weight) and the payload you load into it. In practical terms, vehicles are categorized by GVWR into light-duty, medium-duty, and heavy-duty classes. Light-duty typically encompasses GVWR up to 14,000 pounds, medium-duty spans from 14,001 to 26,000 pounds, and heavy-duty includes anything over 26,000 pounds. This categorization is more than a label; it informs licensing, insurance requirements, inspection regimes, and how a vehicle is taxed in many jurisdictions. A ladder rack, placed atop a pickup or utility truck, is an accessory that can meaningfully expand what the vehicle can transport. It can enable tradespeople to haul ladders, long pipes, or bulky poles with greater ease. However, the rack’s presence does not alter the GVWR or the weight-based class by itself. The rack is a tool; the weight and the way that weight is used are what count.

Consider a typical medium-duty scenario: a bucket truck or a large walk-in van often sits in the 14,001–26,000-pound GVWR range. In this band, the vehicle is already aligned with commercial operations—urban utilities, service fleets, or equipment haulers. The ladder rack adds value for those tasks by enabling efficient transport of extendable items without overloading the vehicle or compromising maneuverability. Yet the same rack on a compact pickup with a GVWR near 6,000 to 8,000 pounds does not elevate the vehicle into the medium- or heavy-duty category. It remains a light-duty truck with a functional upgrade. The crux is simple on the surface, but the implications run deep: the rack improves capability, not the classification ladder itself.

This nuance matters once you move from the shop floor to the road. If a truck is used regularly for business purposes—contracting, landscaping, electrical work, or delivery services—then the business use can trigger commercial considerations, regardless of the rack. The vehicle’s classification, and the regulatory and insurance framework that accompanies it, often depends more on use patterns and GVWR than on aftermarket accessories. In practical terms, a light-duty pickup with a ladder rack could still be carrying tools for a full-time business, and that use could subject the vehicle to commercial vehicle standards and insurance requirements that would not apply to a purely personal vehicle. Conversely, a truck destined for personal weekend projects but equipped with a ladder rack remains within its designated GVWR class and does not automatically enter commercial status simply because the rack is installed.

The relationship between purpose and category is further clarified when we examine how regulations are applied in the real world. The presence of a ladder rack can indicate intent—an operator who routinely hauls ladders and long items for work. But the enforcement lens often focuses on weight, usage, and fleet context. When a vehicle is primarily used to earn income, or when it is registered and insured under a commercial policy, many jurisdictions treat it as a commercial vehicle. This can unlock a set of requirements—expanded insurance coverage, commercial licensing or registration specifics, and different compliance expectations—that would not necessarily apply to a private-use vehicle of similar size. In short, purpose matters as much as payload.

For those navigating these waters, it helps to consider the broader picture: how weight interacts with utilization. A ladder rack increases payload efficiency for long items and can improve on-site productivity by reducing the need for multiple trips. Yet productivity does not automatically equate to commercial status unless paired with ongoing business activity and appropriate policy and regulatory alignment. The critical takeaway is that the ladder rack amplifies the truck’s operational versatility, not its regulatory category. It is the sustained business use, the vehicle’s GVWR, and the policy framework surrounding it that drive classification. In this sense, a light-duty pickup with a ladder rack can support commercial work without ceasing to be a light-duty vehicle, while a medium- or heavy-duty truck outfitted with racks can still be counted as commercial based on weight and use, not merely on its cargo-carrying accessory.

The practical upshot for owners and operators is to examine two parallel tracks. First, verify the GVWR of the vehicle and how it aligns with the kind of work being performed. The GVWR is the gatekeeper that determines the broad class and many of the downstream requirements. Second, scrutinize the actual usage pattern: Is the truck routinely engaged in business activities, transporting tools or goods for profit, or part of a larger fleet? If the answer to either of these questions tips toward business use, then it is prudent to anticipate the regulatory and insurance implications that accompany commercial operation—an awareness that often governs licensing, registration, and coverage more than the mere possession of a ladder rack. For readers seeking a concise regulatory checkpoint, professional guidance from the local Department of Motor Vehicles or relevant transportation authority remains the recommended route. In contexts where cross-border or regional regulations intersect, resources such as online discussions and regulatory briefings can illuminate how authorities view these distinctions across jurisdictions. For a perspective that touches on cross-border regulatory considerations, see the discussion on the cross-border regulatory issues event.

The weight of the argument rests not on the rack but on the vehicle’s backbone and the mission it serves. The ladder rack is a practical enhancement that expands what you can carry and how efficiently you can operate. It does not, by itself, rewrite the vehicle’s classification. A medium-duty truck with a ladder rack continues to carry the weight-of-class logic that governs every fleet decision. A light-duty pickup with the same rack remains in its light-duty lane, even if the rack boosts its daily output for a painting job, a ladder installation, or a seasonal haul. This layered understanding helps clear the fog around classification and links the decision to something tangible: the GVWR and the usage pattern.

In practice, many operators balancing cost, compliance, and productivity take a pragmatic approach. They assess whether the extra capacity and safety that a ladder rack affords justify the potential shifts in regulatory expectations. If a business is growing and the vehicle moves into or near the higher GVWR zone, it may be worth reevaluating insurance coverage, registration, and driver qualifications to ensure that the compliance framework keeps pace with operational reality. If, however, the rack is simply a tool for occasional heavy-lifting on a personal project, it is reasonable to maintain the vehicle’s existing classification and policy structure while enjoying the added functionality. The clarity comes from recognizing that the ladder rack is a capability, not a category, and that the classification is anchored in weight and use rather than appearance.

For readers seeking deeper technical and regulatory insight, the broader discussion around ladder racks and their impact on vehicle use can be complemented by case studies and regulatory briefs available through industry discussions. These resources help illuminate how regulators approach vehicle classification in diverse contexts, from urban service fleets to regional transportation networks. And while the rack features a practical value story, the regulatory journey remains rooted in the fundamentals of GVWR and purpose. When in doubt, a cautious path is to align vehicle use with the appropriate policy and regulatory framework, ensuring the rack continues to serve as a reliable asset rather than a source of compliance ambiguity.

External resource for further reading on ladder rack specifications and performance can be found here: https://www.truckracks.com/blog/truck-hitch-ladder-rack-specifications-performance-and-common-uses.

[Note: Internal reference to regulatory context and cross-border considerations can be explored further at the cross-border regulatory issues event page.]

Ladder Racks and the Commercial Status Debate: When Accessories Signal Utility, Not Identity

A ladder rack is a practical accessory on many work trucks. It expands capacity, keeps long tools secure, and streamlines daily tasks. Yet its presence does not by itself declare a vehicle commercial. Classification hinges on how the vehicle is used, who uses it, and how it is insured and registered in relation to business activity. The rack functions as a lens through which the line between personal and commercial use is viewed: the primary use determines classification more than any single feature. When a truck serves a trade, service, or revenue generating operation, the rack often reinforces its commercial character, enabling faster, safer, and more efficient on site work. The practical impact goes beyond convenience; for tradespeople the rack secures ladders, long poles, and other items without cluttering the cab and reduces downtime, while integrated storage options can turn a rack into an organized system for field work. Industry perspectives emphasize that while a rack alone does not convert a personal truck, combined with regular business usage, inventory transport for profit, and service delivery it signals readiness and reliability to clients and regulators. Permanent ladder racks bolted or welded to the frame offer stability and durability for fleets that rely on long items, and they can contribute to a professional image that aligns with client expectations of reliability. In practice, a well configured vehicle with a ladder rack communicates organization, preparedness, and discipline, which can influence bidding, scheduling, and repeated business. Ultimately classification rests on usage patterns rather than hardware: if the truck is used regularly for business tasks, carries tools and crew, and is insured and registered as part of a fleet or business, it is more likely to fall under commercial vehicle considerations. Conversely, a truck used mainly for personal errands, even with a rack, is less likely to trigger commercial status unless use patterns change. For professionals navigating cross border or multi jurisdictional contexts, consult local authorities and insurers to map use to coverage and classification. See notes on cross border regulatory issues as context for how fleet classification can vary and how equipment, use, and coverage should align with evolving standards. In short, a ladder rack is a tool that, when paired with disciplined workflows, reinforces the vehicle’s role as a service asset rather than a private conveyance, and the resulting regulatory treatment follows from actual business use.

Racks, Rules, and Responsibility: Navigating Regulation and Insurance for Trucks with Ladder Racks in Commercial Use

A ladder rack on a pickup or utility vehicle does not automatically reclassify the truck as a commercial vehicle. The question hinges on how the vehicle is used, who operates it, and the regulatory or insurance lens through which it is viewed. A ladder rack is an accessory designed to transport long, heavy items—ladders, lumber, pipes, kayaks, or surfboards. In many cases, a truck used for occasional work or personal projects remains a private vehicle with aftermarket gear. Yet when a truck becomes a reliable tool of daily business, the line between private use and commercial operation can blur quickly. A contractor who uses the rack every day to haul ladders to job sites, a landscaper who carries long timbers, or a technician who visits multiple commercial sites with equipment in the rack is likely to be evaluated under commercial vehicle rules. The presence of the rack matters less than how the vehicle is used, how it is registered, and how it is insured. In this sense, the ladder rack can symbolize professional activity, but it does not by itself dictate classification.

From a regulatory perspective, the core concern is safety within the framework of established standards for all cargo on the road. The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration sets clear expectations for cargo securement, and those standards apply to items mounted on external racks as much as to loads inside a trailer. The rack may be sound, but the items it carries must be secured so they cannot shift, fall, or create hazards for other road users. The overarching principle is straightforward: secure every piece of cargo so it cannot become a hazard. The rack’s interaction with the vehicle’s stability and handling matters too. A load that shifts or loosens under vibration can alter the center of gravity, increasing the risk of loss of control during lane changes or in gusty conditions. This risk calculus underpins the emphasis on proper installation, ongoing maintenance, and diligent load securement.

Another important dimension is the vehicle’s dimensions. Ladder racks that extend beyond the vehicle’s body can push a truck outside legal length or width limits. Regulations typically place caps on overhang, often around three feet beyond the front or rear of the vehicle, though exact limits vary by jurisdiction. Overhang is not merely a paperwork issue; it translates into real-world safety concerns on busy highways, especially at night or in adverse weather. When racks extend, they can interact with other vehicles or infrastructure in unpredictable ways. In some contexts, even mounting points can become liabilities if they do not meet design specifications or if they alter the certified weight of the vehicle.

Safety inspections test more than cosmetic fit. Inspectors look for robust installation, sound mounting hardware, and signs of fatigue or corrosion in anchors. A rack or its fasteners that show wear may trigger violations, even if the load itself is properly secured. Regular inspections become part of a broader risk management program, not just a one-off hurdle. A fleet that neglects these checks invites increased scrutiny at roadside stops and faces penalties, required corrective actions, or disruptive downtime that erodes productivity.

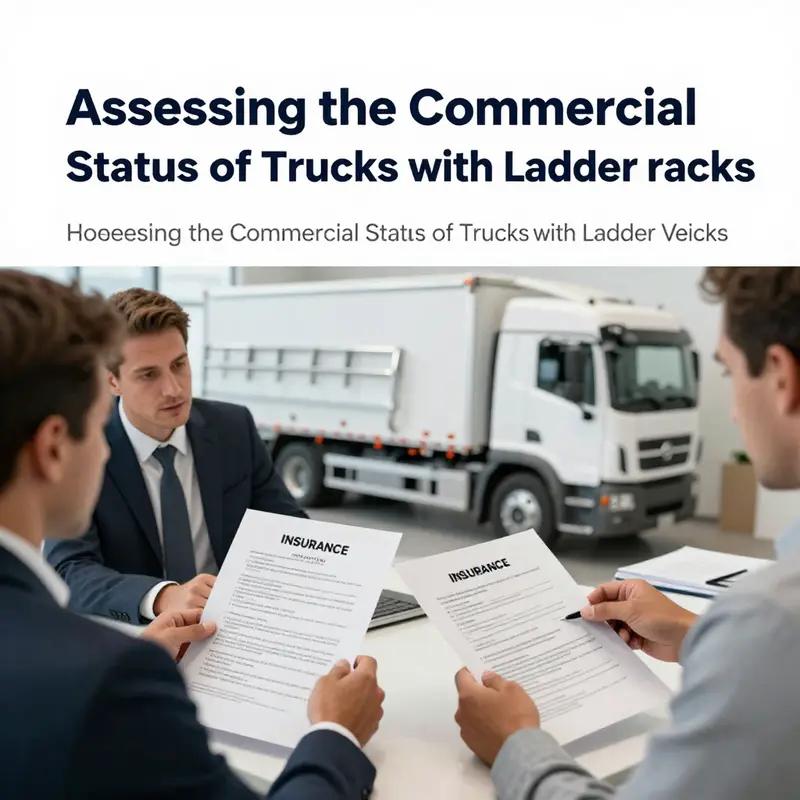

Insurance adds another layer of complexity. Providers treat ladder racks as aftermarket modifications that can alter a vehicle’s risk profile. The presence of a rack can lead to higher premiums unless it is properly disclosed and underwritten. Insurers commonly request proof of correct installation by a certified technician and documentation of load-securement practices. Maintenance records showing the rack remains secure and that tie-downs and anchors are intact may become part of the policy. Some policies may exclude damage caused by unsecured loads or modifications unless the endorsements are explicitly included. In short, a claim could be denied if the insurer determines negligent setup or a failure to follow safe loading procedures. The risk assessment extends beyond a single accident to potential liability for third parties or property damage caused by a protruding rack or a falling load.

To address these risks, a proactive stance is essential. Businesses should consult with legal counsel versed in transportation and safety regulations, as well as with insurance brokers who understand commercial auto policies and aftermarket modifications. Driver training becomes a frontline defense: workers should know how to secure loads, perform pre-trip inspections, and recognize when a load or rack is not fit for travel. A rigorous pre-trip checklist helps ensure fasteners are tightened, the ladder is anchored securely, and nothing extends beyond permitted dimensions. Documentation matters: keep installation records from qualified technicians, ongoing maintenance logs, and periodic audits of load-securement practices. When ladder racks are part of a service model, pursuing specialized commercial auto coverage that explicitly accounts for aftermarket accessories can provide clearer liability protections. Such coverage can address a broader set of risks, including non-driving incidents like damage from a stalled or parked vehicle with a protruding rack.

Classification decisions often hinge more on usage patterns than on the mere presence of equipment. A truck regularly used for business, registered to a company, and insured under a commercial policy is typically treated as commercial, even if the rack is present. The decision can involve how the vehicle is recorded for tax purposes, whether it sits within a fleet, and how it is accounted for in internal asset management. In practice, the line between personal and commercial usage can blur as small businesses grow, but misclassification can carry meaningful consequences. Mislabeling may affect registration fees, licensing, and the scope of safety and driver regulations that apply, depending on the jurisdiction. The goal is not to stigmatize a simple ladder rack, but to acknowledge how its presence interacts with a broader regulatory and insurance framework that governs how, where, and by whom the vehicle is used.

From a policy perspective, the prudent approach blends operational flexibility with discipline in compliance. A governance framework that clearly defines when a vehicle is used for business, when it is used for personal errands, and how the rack is treated as part of the vehicle’s overall safety system helps keep operations smooth. This means driver training, maintenance schedules, and a process for updating permits or registration status as business use expands. It also underscores the value of targeted guidance and the benefit of consolidating federal and state expectations into a practical standard. The discussion here aligns with a regulatory landscape that recognizes cargo securement, vehicle dimensions, and the safety of those who share the road with heavy, ladder-laden loads.

For readers navigating these questions in real time, a concrete starting point is to explore the cross-border regulatory landscape, since many operations span jurisdictions with different rules. See TCAS cross-border regulatory issues event for a sense of how regulators discuss these matters in practice, especially when a fleet crosses geographies. This kind of cross-cutting discussion helps frame the issue beyond a single highway or state line and underscores the need for a holistic compliance posture that scales with business growth. While the event itself is a reminder of complexity, it also spotlights practical steps—training, documentation, and consistent safety checks—that can protect a company as it uses ladder racks as a tool for productivity rather than a trigger for friction with regulators or insurers.

The overarching message remains: a ladder rack does not automatically classify a truck as commercial; what matters is how the vehicle is used, how it is insured, and how well its loads are secured within a regulatory framework. When these elements align, a truck with a ladder rack can operate within the same safety and regulatory boundaries that govern other commercial activities, delivering the needed balance between operational flexibility and public safety. For official guidance, consult the FMCSA regulations and related federal resources that define cargo securement, vehicle dimensions, and equipment modifications for commercial operations.

Ladder Racks and Classification: How Vehicle Use Shapes Costs for Work Trucks

A ladder rack on a pickup or a utility vehicle is a familiar sight in many trades and neighborhoods. It signals capability and versatility, a simple accessory designed to carry long items like ladders, poles, or bulky gear without crowding the cab. Yet the fact that a ladder rack is present does not automatically push a truck into a commercial category. The critical question is not the rack itself but how the vehicle is used, and in what regulatory or economic context that use is evaluated. Insurance forms, vehicle registrations, tax codes, and safety regulations all apply different lenses to the same vehicle, and those lenses sharpen or soften the costs associated with ownership and operation. In practical terms, a truck with a ladder rack can be a personal vehicle, a business tool, or a hybrid of both, and the distinction has real bottom line consequences. The ladder rack becomes a symbol of intent; the underlying use determines the classification, and classification, in turn, determines what counts as allowable expense, what rate of insurance is appropriate, and which regulatory path a vehicle will follow.

The decision point centers on primary use and context. If the truck is used primarily for personal tasks and occasional light hauling, the rack is simply an accessory. If, however, it is part of a steady workflow for a business that moves tools, materials, and goods to jobsites, the rack becomes part of a business asset that signals commercial activity. This distinction matters across jurisdictions and regulatory regimes because the same physical vehicle can be treated differently depending on how its duties are framed. In some places the threshold is as simple as the regularity of business hauling; in others it relies on formal fleet status, commercial insurance, or a business license tied to the vehicle. The upshot is straightforward: the rack is not a classifier, but the use pattern attached to the rack is.

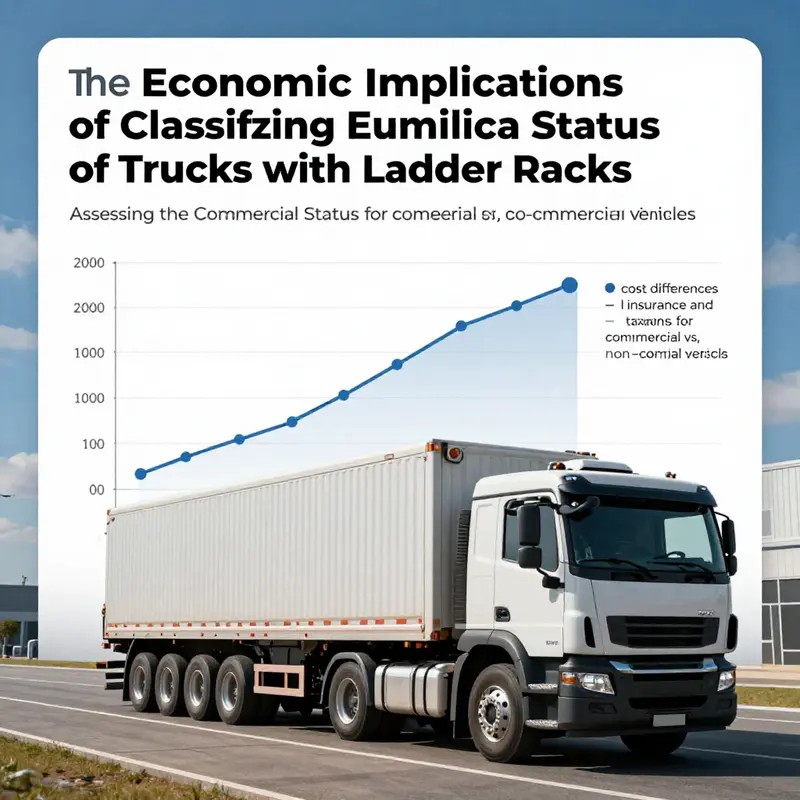

From this perspective, the ladder rack becomes a lens into broader economic dynamics. The chapter that follows the overview of how classification works in practice shows that the economic implications extend beyond a single line item in an insurance quote or a registration bill. They touch the cost structure of a small business and, in aggregate, the economics of the broader market for service work. A truck with a ladder rack may wind up in a higher tax bracket, pay higher registration fees, or carry a different insurance premium because it is viewed as a tool used to transport goods to revenue-generating activities. Across both the United States and the United Kingdom, classifications influence the financial calculus of ownership, and those calculations shape the viability of individual enterprises and the choices they make about fleet composition.

Tax implications sit at the center of this calculus. When a vehicle is classified as commercial, it is typically recognized as a business asset used to generate income. That recognition can unlock deductions for depreciation, fuel, maintenance, and other operating costs that match the business use of the vehicle. In return, the business may face higher annual fees tied to the vehicle’s commercial status and, in some jurisdictions, a higher vehicle tax or registration charge. The dimensions of this balance shift with geography, but the logic holds: the classification alters the tone of the cost ledger. The same truck that would be treated as a personal conveyance in one context may be entered into the business accounts in another, with corresponding effects on how expenses are deducted and how revenue-generating activity is reported to tax authorities.

Insurance follows a parallel logic. Insurers price risk, and they differentiate between personal and commercial usage because the exposure patterns diverge. A truck that carries work-related tools and materials and makes regular trips to multiple sites presents different risk characteristics than one used primarily for commuting and leisure. Commercial classification often translates into higher premiums, broader liability coverage, and different terms for claims. For a small business or an independent contractor who relies on such a vehicle to keep a paycheck, these premium differentials can be a substantial ongoing cost. Yet the same framework that elevates premiums also opens doors to coverage tailored to business risk, which can be protective in the event of a claim arising from professional activity. In other words, there is a trade-off embedded in the pricing logic: higher costs in some lines of the ledger, but the potential for more appropriate risk protection and more accurate accounting of business use.

A related but equally important dimension is the possibility of tax deductions tied to business classification. When a vehicle is properly recognized as a commercial asset, the expenses tied to its operation—fuel, maintenance, tires, depreciation, insurance—can typically be allocated to the business and claimed accordingly. This can offset the higher outlays that come with commercial status. But the flip side is real: misclassify or blur the boundary between personal and business use, and the penalties or audit risks can erase or exceed any marginal tax relief. The governance of classification thus becomes a strategic discipline, one that requires careful record keeping and a clear picture of how the vehicle is used across the year. The risk of ambiguity is not trivial; it is a friction cost in itself, potentially exposing a business to penalties or retroactive adjustments that complicate profit calculations and cash flow.

These dynamics are not abstract. They interact with how a business makes decisions about what kind of truck to buy, how to insure it, and how to allocate budget for fleet maintenance. A ladder rack adds capacity and flexibility, yet it also invites closer scrutiny of usage patterns. If a contractor acquires a truck specifically to support a commercial operation, the economic argument for classifying the vehicle as commercial strengthens. If the rack is merely a convenience for a passion project or sporadic weekend work, the commercial label becomes harder to justify. In mixed-use scenarios where a truck serves both personal and business duties, the classification question becomes a question of proportion and control—how much time and money are dedicated to business use, and how clearly can that use be documented and demonstrated to authorities and insurers.

The cross border texture of these decisions reinforces the point. In the United States and the United Kingdom, the connective tissue of classification—how use maps to taxes, registration, and insurance—creates a pragmatic frame for small businesses to operate within. The UK guidance is explicit about how commercial vehicle classification interacts with licensing and regulatory expectations, underscoring that accuracy in classification is not merely bureaucratic formality but a central economic decision. Across the Atlantic, the U S Department of Transportation and related agencies emphasize a similar logic, where the status of a vehicle has ramifications for regulatory compliance, safety standards, and the financial obligations of ownership. The shared principle is that context matters more than form; the ladder rack is a feature, the usage pattern is the determinant.

For readers seeking a broader context on how fleet decisions evolve with market conditions, it is helpful to consider how capacity dynamics shape equipment and scheduling. In markets where excess capacity persists, operators may be more sensitive to total vehicle cost and regulatory friction as they optimize margins. Conversely, in tighter markets, the cost of misclassification can loom larger as margins compress and regulatory scrutiny tightens. The thread that ties these observations together is an understanding that classification is not a single checkbox but a decision that reverberates through the cost structure of an operation. A practical takeaway for practitioners is to align classification with documented usage, to maintain records that separate personal from business activity, and to evaluate insurance options that match the declared use. This alignment protects cash flow and reduces the risk of penalties while preserving the liquidity needed to invest in the equipment that keeps work moving.

To connect these ideas with ongoing industry conversations and market intelligence, consider how fleet economics interact with capacity dynamics in broader markets. For deeper exploration, see the discussion on Excess capacity insights. By situating the ladder rack decision within the larger story of fleet utilization and regulatory expectations, business owners can approach classification not as a constraint but as a strategic lever that can improve profitability and resilience. In the end, the ledger should reflect the reality of use, not the shape of the rack. When it does, the chapter on ladder racks and classification becomes a straightforward part of prudent fleet management rather than a source of recurring uncertainty.

External resource for official guidance on commercial vehicle classification and licensing is available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/commercial-vehicle-classification-and-licensing

null

null

Final thoughts

Tightly linked to the operational context, understanding whether a truck with a ladder rack is classified as commercial is essential for procurement teams, fleet managers, and business owners alike. The classification hinges not just on the physical attributes of the vehicle but significantly on its intended use and the regulatory framework that governs its operation. By navigating the dimensions of usage, regulatory compliance, and economic impact, stakeholders can make informed decisions to optimize their vehicle fleet. This ensures compliance while also recognizing the potential for cost savings in insurance and operational efficiency.